Since the late 1800s, aquascaping has become a progressively popular form of art among those in the aquarium-keeping hobby. No longer do serious hobbyists simply lay some sand or gravel at the bottom of a tank, place a few decorative ornaments, and call it a day. These aquarists have cultivated a community of artists that create natural ecosystems as living works of art within the confines of a glass aquarium. Aquascaping is the art of methodically arranging aquatic plants, rocks, wood, and substrate, in a specific stylistic manner. Simply said it is the art of underwater gardening, but creating any type of aquascape requires the artist to have abundant scientific knowledge. Without proper water parameters and knowledge of various plant and aquatic species, the aquascape will quickly decompose. Because of the innate relationship aquascaping has with art and science, it can communicate and spark conservation efforts among serious aquarists. Therefore, by creating aesthetically pleasing underwater gardens as works of living art, aquarists create a relationship between art and science while increasing conservation ethics. This all starts with an artist choosing what style of aquascape they want to create. There are various styles that guide the design process and different styles come with different goals that the artist strives to achieve.

Three of the most prominent styles are iwagumi, the nature aquarium, and biotope. Iwagumi translates from Japanese to mean “rock formation” and tends to be the most visually minimalistic style. Unlike other styles, the main goal of an iwagumi aquascape isn’t necessarily to emulate a real-looking environment, but rather to create a perfectly balanced arrangement of stones. This harmonious style is heavily based on mathematics and is achieved by following the golden ratio or the rule of thirds. The golden ratio is a unique mathematical proportion often found in nature that has been theorized to be the most aesthetically pleasing to the eye. According to the golden ratio, a stone should have a length roughly one-point-six times its width. The rule of thirds helps the artist in organizing the arrangement by dividing the composition into thirds both vertically and horizontally. Stones should be placed along the hypothetical lines or points where the lines intersect. Iwagumi aquascapes always utilize an odd number of stones to avoid symmetry and place importance on the scale of each stone in relation to the other. This style was developed by Takashi Amano, a well-known photographer, and aquarist. Amano always took fine details into great consideration when building his aquascapes and once said that “to know Mother Nature, is to love her smallest creations.” His appreciation for nature and cultural background lead him to create the iwagumi style.

Amano’s untitled iwagumi piece from 2009 features an arrangement of three senmigawa stones planted on a bed of low-laying aquatic plants known as carpeting. The primary stone in the center of the composition is called Oyaishi. This stone is always the largest and acts as the focal point of the piece. Often times it is also placed slightly tilted in the direction of water flow to mimic the position of natural river rocks. To the left of Oyaishi is Fukuishi, the second largest stone and often resembles Oyaishi in color and texture. This stone is used to balance the primary stone and create tension in the composition. Lastly, on the right side of Oyaishi is Soeishi, the smallest of the three stones and is used to accentuate the strength of the primary stone. This arrangement satisfies the golden ratio and pays tribute to traditional Japanese concepts of culture and simplicity as seen in other types of Japanese gardening like zen rock arrangements. The carpet of Amano’s piece is made up of echinodorus tenellus, located on either side of Oyaishi between the outer two stones, and hemianthus callitrichoides in the surrounding scape. Although this style is visually minimalistic and may appear to be simple to recreate, to do so successfully is very difficult requiring extensive knowledge of related mathematics.

To maintain such an aquascape is even more difficult, the artist must also understand the scientific factors. The aquatic plants most commonly used in this style of aquascape are heavy root feeders, meaning they grow intricate root systems that require additional fertilizer in the substrate. The artist must choose a substrate that can account for this need such as aquarium soil which is rich in nutrients or use the water column method by adding additional liquid plant fertilizer. The biggest issue most aquarists who attempt this style face is algae formation. To battle this, aquarists must be cautious in their choice of water filtration, lighting, and tank nutrients. Too much light or excessive nutrients and the algae will rapidly grow. A proper water filtration system is also key to balancing water parameters and avoiding such algae growth. The delicate balance of math and science makes an iwagumi aquascape both difficult to create and maintain.

Unlike iwagumi, the goal of a biotope aquascape is to perfectly emulate a natural environment both visually and physically on a scientific level. For a successful biotope, accuracy is key. Elements include creating authentic water conditions and choosing aquatic plants and hardscapes native to the environment being recreated. Aquarist Zhuang Yi utilizes this style in his piece promptly titled Underwater Caves in the Peninsula of Yucatan, Mexico. This aquascape imitates the environment found in the underwater caves in the peninsula of Yucatan, Mexico. The scape includes an assortment of stalactites that enter the composition from the top and bottom with water that appears to have a blue tint. The artist also added a possum skull which he placed on top of the substrate between stalactites and added blind cavefish to inhabit the scape. The artist’s inspiration for this piece stems from the fish which naturally inhabit this type of environment. He says, “The first time I saw blind fish, I was deeply attracted, so I looked up a lot of information and decided to restore the Maya underground cave in Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula. There are a lot of mammal bones in the cave, so they stay in the water for years, and I used a possum skull in the water to simulate them.” In 2020, this aquascape won first place in the 96L Biotope Aquascape category of the Aquatic Gardeners Association International Aquascaping Contest. However, one judge pointed out that the piece, “suffers from a lack of biodiversity. Cenote ecosystems are special because in part of the community of organisms that live there. Including only one species of fish is not a complete biotope.” The judge who made this observation, Ted Judy, carries forty-plus years of experience keeping aquariums, and his comment proves just how serious accuracy is to this style of aquascape. In order to ensure the artist captures the environment accurately, many times they visit the location or a similar environment to fully understand its natural composition. Prior to the creation of this piece Yi visited many local caves to get a true “feel” for the stalactites in the environment. However, it is unclear whether or not the artist utilized real stalactites for his aquascape or if they are man-made replicas.

Alex Wenchel’s Flooded Forest Tributary of the Rio Negro, which won first place in the 2021 90L Biotope category of the Aquatic Gardeners Association International Aquascaping Contest, is another exceptional example of a biotope aquascape. This biotope represents a flooded forest floor which the artist witnessed while on a trip to see the small tributaries of the Rio Negro River, the largest remaining tributary of the Amazon River. It utilizes materials such as “fallen” logs, leaf litter from a willow oak, and blended almond leaves among other botanicals. This piece displays the process of decay encapsulated by clear amber water. The amber water gives this piece warmth and the several “fallen” logs and stumps create various shadows within the scape. Aquarists like Wenchel who utilize shadow in their composition achieve a dramatic effect that can create a feeling of suspense, mystery, or moroseness. The shadows of Wenchel’s biotope are fitting with the theme of decay which resonates with the gloomy feelings one may feel while viewing this piece.

Although Wenchel’s piece explores the theme of death and decay, it still required the artist to carefully consider the science behind his tank’s water parameters. He shares that, “While the water is a crystal clear amber, a layer of mulm coats everything, and the slightest disturbance will fill the water with flecks of brownish grey.” Mulum is the layer of debris formed by the decomposition process of organic materials. This layer of mulum sits on top of all of the elements found within Wenchel’s piece and even the slightest touch or blow will send particles floating, damaging the appearance of the crystal clear water. Both the clear amber water and mulum are elements of Wenchel’s composition and he manages to have both in the same space without disturbance, but there is more to consider when it comes to mulum. Because mulum is a waste compound it can create harmful levels of nitrogen which can harm any live aquatic animals in the tank. This piece harbors cardinal tetras as inhabitants, meaning it’s important to keep nitrates low for the health of these fish. To prevent the adverse effects of mulum, the artist must have enough biological filtration such as beneficial bacteria to break down the nitrogen waste. The artist also recognizes that the size of his tank and quantity of fish will also have an effect on water parameters. The artist chose to include only ten tetras in his biotope due to the limited size of the tank. More fish means more waste being produced which must be accounted for. If too many fish are placed in a single tank it can have detrimental effects on the water parameters causing spikes in ammonia and nitrates, preventing the fish from being able to survive. Wenchel’s careful attention to such scientific aspects within his tank is an indication that his biotope is a success. His biotope meets the goal of creating a truly thriving ecosystem that can support live aquatic animals and process organic waste without affecting water quality.

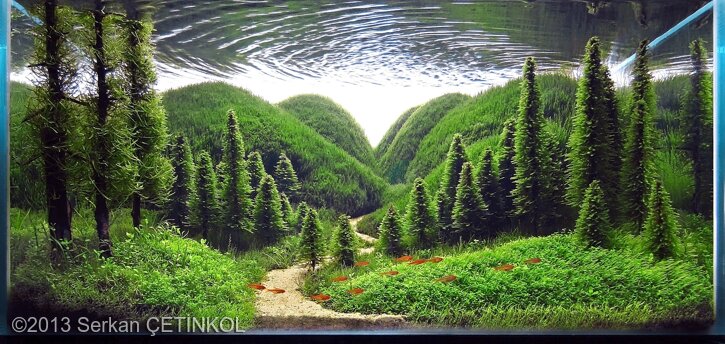

Unlike the biotope style, the nature aquarium style does not strive to accurately represent an underwater ecosystem. The basis of this style is recreating terrestrial landscapes such as mountains, valleys, and deserts among other environments one would normally see above water. These styles of aquascapes tend to have many different species of plants and elements to convincingly create a realistic environment. The nature aquarium style also tends to be the one that receives the most attention from viewers due to its whimsical traits and is a popular focus of many aquascaping competitions.

Whisper of the Pines by Serkan ÇETİNKOL shows just how incredible this style truly is. This aquascape resembles a mountain valley with pine trees, hiking paths, and mountains. The artist uses a concave shape layout which places the height at the sides and a central lower point in the center to guide the viewer’s eye to the path created by the artist with sand. The path weaves its way from the foreground all the way into the background until it is no longer visible. This leads the viewer’s eye to the focal point and creates a sense of depth within the composition. The ability to create a sense of depth is a sought-after element utilized by advanced aquarists. However, to create such an aquascape requires the artist to have considerable knowledge of aquatic plant species to create a realistic-looking mountain valley. The plants and materials used in this piece include taxiphyllum barbieri, vesicularia dubyana, taxiphyllum sp. flame, utricularia graminifolia, glossostigma elationides, hemianthus callitrichoides, ammania sp. bonsai, eleocharis parvula, leptodictyum riparium, and various sands. ÇETİNKOL’s knowledge in botany led to his choices in plants to be a success in creating a sustainable environment within the tank.

A similar aquascape titled Wild West by Stjepan Erdeljic although vastly different in theme of terrestrial landscape, shares its requirement of deep botanical knowledge. The plants and materials used in this piece include java moss, flame moss, fissiddens fontanus, HC cuba, elocharis parvula, gravel sand, stones, and “DIY cactus material.” Aquarists who utilize a variety of aquatic plants to densely fill their composition must also be aware of the nitrogen cycle. Aquatic plants effectively use nitrogen and can incredibly diminish the degrees of nitrate in a balanced aquarium. Meaning that these aquascapes benefit from the presence of aquatic wildlife to naturally continue on the nitrogen cycle. Erdeljic’s nature aquarium resembles a scene such as those found in the Arizona deserts. To compose this aquascape Erdeljic opted for a triangle shaped layout which creates a gradual slope from left to right. This composition gives the aquascape realistic variation in landscape elevation, verisimilar to that which would be seen in a real desert. The tiny yet realistic-looking cacti found scattered across the desert-scape are formed by shaping and grooming aquatic plants into a cactus-like shape. This addition makes the theme of the aquascape immediately recognizable to the viewer and adds to the success of this piece. Both Erdeljic and ÇETİNKOL achieve success in creating miniature underwater versions of our world above water in tandem with botanical science.

Not only do these aquascapes create visually captivating works of art and explore elements of science, but according to Elizabeth A. Marchio (a researcher from Texas A&M University), they also work to communicate conservation ethics. Conservation ethic is the moral way of thinking and preservation zeroed in on shielding species from elimination, restoring natural habitats, upgrading environment benefits, and protecting diversity among biological elements. In the study which Marchio conducted, she found that “(1) caring for a home aquarium communicates science latently, (2) over time, latent science communication becomes activated, and (3) long-term aquarium keeping leads to a personal response in science, as well as conservation.” Marchio shares that aquarists new to the hobby, and those with a relaxed direction, know nothing about protection suggestions and tend to participate in unwanted behavior. Such conduct includes buying species that become excessively enormous for tank captivity, buying creatures without first exploring their requirements or needs, overloading an aquarium, and so on. Public web forums have consistent and enthusiastic discussions, regarding these matters. Unlike novice aquarists, experienced aquarists comprehend the significance of granting a preservation ethic to new aquarists. Marchio says that “It seems it is up to the aquarium community to “police” the consumption and behavior of other aquarists.” The individual meaning of science and preservation realities is affected by “cultural, social, and political conditions in which they are produced and/or promoted.” Further, it is basic to include all aquarists in logical correspondence to contextualize and outline their collaborations with the captive ecosystem and its inhabitants. Marchio believes that gatherings of individuals interested in the aquarium keeping hobby, like clubs and meetings, are ideal spots to work on a science and preservation ethic. Zhuang Yi’s aquascape Underwater Caves in the Peninsula of Yucatan, Mexico (fig 2) is an important example of how aquascaping sparks conversation about conservation efforts. As mentioned previously, it is unclear whether or not the artist used real stalactites to create his biotope. If the artist did in fact utilize real stalactites which he harvested from a natural cave would mean having destroyed a structure which took over a thousand years to form. If everyone harvested pieces of underwater caves, the natural habitat would go extinct creating a detrimental effect on the local ecosystem. This makes it typically illegal to touch or harvest such things as stalacites from caves. The judges reviewing his work expressed their concern over the idea of using real stalacites and informed Yi of the potential implications his behavior had on conservation.

From mathematically intricate aquascapes, to those that accurately recreate underwater environments, and those which mirror the world above water, each utilizes elements of art and design concurrent with scientific processes. These artists continue to push the boundaries of what is possible to create within constricted and initially sterile glass aquariums. This continuation of innovation in design has popularized aquascape competitions around the world and intrigued many in the art form. The community formed around the art and hobby of aquarium keeping has communicated scientific knowledge and morals of conservation among those who are experienced and new to the art. Such conversation and practices of conservation will lead to a better practice of aquascaping.

Sources

Bearly, Irene. “What Is Mulm or Detritus in Aquariums?” Aquarium Co-Op, October 19, 2020. https://www.aquariumcoop.com/blogs/aquarium/mulm.

“Bio-Ted-Judy.” Raleigh Aquarium Society. Accessed December 11, 2021. https://www.raleighaquariumsociety.org/biotedjudy.

ÇETİNKOL, Serkan, “#427: 150L Aquatic Garden Whisper of the Pines,” AGA Aquascaping Contest, 2013. https://showcase.aquatic-gardeners.org/2013/show427.html.

Duke University. “Mystery of golden ratio explained.” ScienceDaily. http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2009/12/091221073723.htm (accessed December 10, 2021).

Edmond, Adam. “7 Aquascaping Styles for Aquariums.” The Aquarium Guide, May 16, 2019. https://theaquariumguide.com/articles/7-aquascaping-styles-for-aquariums.

Erdeljic, Stjepan. “#248: 160L Aquatic Garden Wild West,” AGA Aquascaping Contest, 2013. https://showcase.aquatic-gardeners.org/2013/show248.html.

Farmer, George. “Aquascaping Styles: Nature Aquarium, Iwagumi, Dutch Aquarium.” Aquascaping Love, 2020. https://aquascapinglove.com/learn-aquascaping/aquascaping-styles/#iwagumi.

“Legendary Aquarist Takashi Amano.” Aquarium Architecture, October 2013. https://www.aquariumarchitecture.com/archive/legendary-aquarist-takashi-amano/.

Marchio, Elizabeth A. “The Art of Aquarium Keeping Communicates Science and Conservation .” Frontiers in Communication 3 (2018): 1–17. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcomm.2018.00017.

Micalizio, Caryl-Sue. “The Golden Ratio.” National Geographic Society. National Geographic Society, November 20, 2012. https://www.nationalgeographic.org/media/golden-ratio/.

Reich, Thomas. “Nitrogen Cycle in Aquariums – Understanding the Basics.” The Spruce Pets. The Spruce Pets, November 27, 2019. https://www.thesprucepets.com/nitrogen-cycle-understanding-1380724.

“The Iwagumi Layout: An Introduction.” Aquascaping Love, August 6, 2019. https://aquascapinglove.com/basics/introduction-iwagumi-layout/.

Wenchel, Alex. “#976: 90L Biotope Aquascape ‘Flooded Forest Tributary of the Rio Negro.” AGA Aquascaping Contest, 2021. https://showcase.aquatic-gardeners.org/2021/show976.html.

Yi, Zhuang. “#448: 96L Biotope Aquascape ‘Underwater Caves in the Peninsula of Yucatan, Mexico.” AGA Aquascaping Contest, 2020. https://showcase.aquatic-gardeners.org/2020/show448.html.