Photography has been used to document important moments for as long as cameras have been around. However, it has begun to transform into a contemporary art form in recent years. With picture-focused social media sites like Instagram and Snapchat being as popular as they are, photography is constantly changing and becoming more integrated into our lives everyday. We get to see into people’s daily lives, and there has been a shift towards desiring authenticity and realness. Documentary photography captures these real everyday events that happen in people’s lives. Documentary photography is a broad term, but the National Galleries Scotland describes it as, “…art which captures a real moment, conveying a message about the world. As opposed to photojournalism, which concentrates on breaking news events, it typically focuses on an ongoing issue or story seen through a series of photographs, drawing attention to difficult or dangerous world issues which require some form of remedial or political action.” Documentary photography can be about anything, as long as it is centered around people. Through this art form, we can learn about history, social issues, and feel connected to people we may not even know in real life.

Documenting important events used to only happen through writing. When cameras were first invented in the early 19th century, people saw this as a new way to pass on pieces of history. The earliest record of documentary photography dates back to the Civil War as this was the first big historical event since the emergence of the camera. There are a plethora of photos of the Union and Confederate soldiers, battles, slaves and ordinary life. One photograph titled Contrabands at Headquarters of General Lafayette shows a group of escaped enslaved people holding wash basins standing in front of a line of soldiers who have their arms crossed, and they are all posed in front of an old house, assumingly owned by General Lafayette. General Lafayette was the Confederate Army general, and it is implied that the soldiers had just captured the slaves standing in front of them. Reading about what the Civil War was like can paint a vague picture in your mind, but photographs like these bring on a new perspective. With documentary photography, people could see the realities of it with their own eyes.

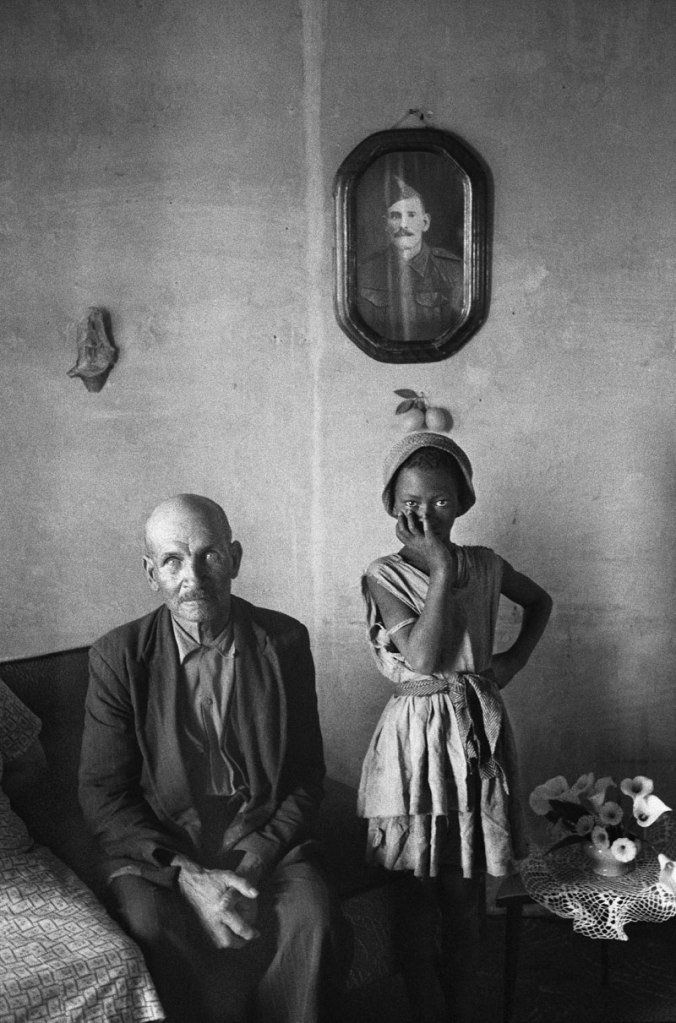

Knowing how powerful documentary photography can be, many photographers decided to use it to inspire social change. David Goldblatt was a South African photographer who documented the effects of apartheid on both Black and White people. To describe the aim behind his photography he once said, “I was very interested in the events that were taking place in the country as a citizen but, as a photographer, I’m not particularly interested, and I wasn’t then, in photographing the moment that something happens. I’m interested in the conditions that give rise to events.” One photograph titled A plot-holder with the daughter of his servant, Wheatlands, Randfontein (1962) depicts an older White man sitting next to a young Black girl. It is clear from this picture they are not close with each other. The man is clasping his hands together while the girl is standing with one hand covering her mouth. They both look visibly uncomfortable standing close to each other. This image illustrates the tension that apartheid has created between everyone. With social media, using photography to spread awareness of social issues has become the norm. In recent events, the riots and peaceful protests that took place after the police killing of George Floyd, an unarmed Black man in May 2020 brought on many powerful photos. For example, protesters in Minneapolis where the killing took place set multiple public buildings on fire in retaliation. In one photo, there is a multi-story building engulfed in flames with billows of smoke coming from the top. There are also two people running away from the building. This picture and others like it went viral, and brought more awareness to the severity of George Floyd’s death and more protests and riots around the U.S. followed suit.

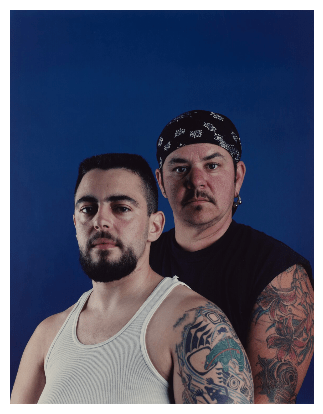

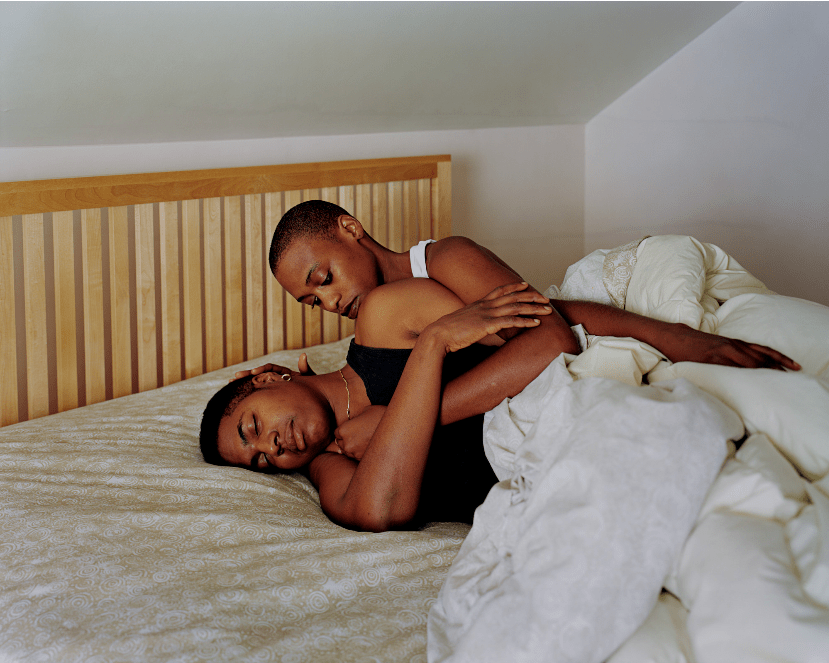

Being able to connect with people like David Goldblatt did is an important part of being a documentary photographer. Not everyone will just allow a random stranger to take their picture. Humans of New York is a photoblog turned Instagram account that focuses on ordinary people’s lives. For this project, photographer Brandon Stanton and his team interview random people off of the street and take casual photos of them. They are never planned or overly edited, and this captures the beauty of everyday people. The subjects are allowed to talk about whatever they want in these interviews, and some people even tell their life story. It gives a sense of humanity to people who you may not know. Photographer Hannah La Follette Ryan has a similar mission with her blog, although she does not usually talk to the people she photographs. Like Brandon Stanton, Ryan also uses Instagram for her documentary photography on the page @subwayhands. Each of her photos is a different pair of hands, or multiple pairs in some cases. Set in a random New York City subway, her subjects are unaware that their hands are being photographed. Journalist Helen Rosner who interviews Ryan states, “The hands that La Follette Ryan captures tell dense emotional stories; in their poses and grips, they take on the surreal semi-humanity of sculpture… They also, over months and years, tell collective stories of what we wear and carry: trends in manicured nails, watches, and rings; new models of phones and headphones. But the story told in her latest photos came on suddenly and is all-encompassing—a collective, simultaneous adjustment in how we interact with the city and with one another.” Although hands may not seem important in pictures, they are. People use them for everything, and they are a huge part of conveying body language. Through her photos, Ryan and viewers of her art and can connect with people without even saying a word.

Documentary photography is centered around people and their lives, whether they are extravagant or mundane. Its importance lies in the fact that it holds pieces of history, inspires social change, and helps us to feel more connected to others.

Sources

Arnold, Brooke. “What is Documentary Photography.” Modula. Last modified December 2, 2021. https://wp-modula.com/what-is-documentary-photography/

ArtNet. “David Goldblatt.” ArtNet. Accessed December 13, 2021. http://www.artnet.com/artists/david-goldblatt/.

Gibson, James F. Contrabands at Headquaters of General Lafayette. 1862. Photograph; 11.5 x 15 cm. Liberty of Congress, Washington, D.C. https://www.loc.gov/item/2014646902/

Goldblatt, David. A plot-holder and the daughter of a servant, Wheatlands, Randfontein. 1962. Gelatin silver print, 21 x 14.1 cm. The Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, IL. https://www.artic.edu/artworks/258962/a-plot-holder-with-the-daughter-of-his-servant-wheatlands-randfontein-transvaal

Kuroski, John. “America’s Darkest Hour: 39 Haunting Photos Of The Civil War.” Ati. Last modified February 24, 2020. https://allthatsinteresting.com/civil-war-photos#2.

National Galleries Scotland. “Documentary Photography.” National Galleries. Accessed on December 13, 2021. https://www.nationalgalleries.org/art-and-artists/glossary-terms/documentary-photography.

Rosner, Helen. “The Anxious Hands of New York’s Subway Riders in the Face of the Coronavirus.” The New Yorker. March 14, 2020. https://www.newyorker.com/culture/photo-booth/the-anxious-hands-of-new-yorks-subway-riders-in-the-face-of-the-coronavirus.

Woltman, Nick. “Protests erupt in Twin Cities over death of George Floyd.” Twin Cities. Last modified May 28, 2020. https://www.twincities.com/2020/05/27/2nd-night-of-violent-protests-over-minneapolis-mans-death/.