At first glance, Dada and Surrealism can easily be mistaken for each other. This is because their styles and motivation behind the art is similar. Both of these movements are meant to make viewers of the art question logic. In her article on Dada and Surrealism, Alice Samusevich writes, “They sought to break down conventions in the arts in order to bring forth a new, improved culture…Surrealism was similar to the Dada movement because it was meant to defy the reason and logic in response to the seemingly unreasonable World War I.” However, if you look past the sometimes questionable, outlandish pieces both movements have to offer, you’ll find that their emergence, styles, and messages are different in a lot of ways.

Dada first emerged in Zurich, Switzerland 1914 as a result of the end of the first World War. As what happens with the end of most wars, countries have to rebuild and there is generally a more serious atmosphere. Many artists started to grow unhappy with the monotony of everyday life. Art historians at the MoMA explain, “For the disillusioned artists of the Dada movement, the war merely confirmed the degradation of social structures that led to such violence: corrupt and nationalist politics, repressive social values, and unquestioning conformity of culture and thought… Dada artists sought to expose accepted and often repressive conventions of order and logic, favoring strategies of chance, spontaneity, and irreverence.” Dada artists were often anti-establishment, left leaning individuals. They proudly rejected the meaning of traditional art and what they felt it stood for. Often, the art world and artists can be seen as pretentious, elitist, and so on. Dadaists, being against the bourgeoisie, rejected these ideas.

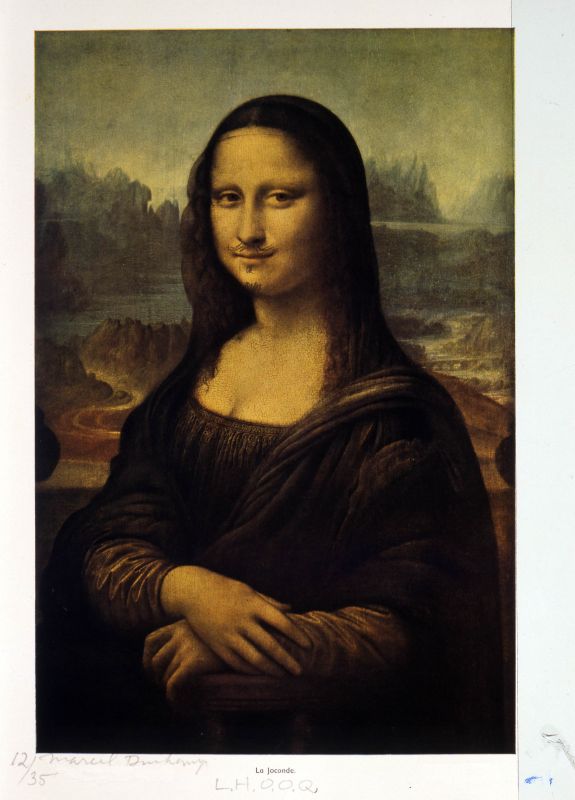

L.H.O.O.Q (1919) by leader of the Dada movement, Marcel Duchamp, depicts the Mona Lisa painting by Leonardo DaVinci with a handlebar mustache and goatee. This is known as a “readymade,” which gives new life and purpose to everyday objects. According to Dr. Charles Cramer and Dr. Kim Grant, “The readymade is divorced from its ordinary context and use value and re-presented in an art world context. This encourages us to encounter the object in a different way.” The piece is meant to be a comical critique of art in general. The Mona Lisa is one of the most iconic paintings in history, today it is worth about $850 million. By making a satirical piece of this piece, perhaps Duchamp was finding the humor in a painting that many people take so seriously.

As Dada art began to dwindle in popularity, Surrealism emerged in Paris in the early 1920s. Similar to Dada, Surrealism was also a response to the first World War. In his article on surrealism, art historian James Voorhies says, “The cerebral and irrational tenets of Surrealism find their ancestry in the clever and whimsical disregard for tradition fostered by Dadaism a decade earlier.” Surrealists wanted to introduce different ideas, and to inspire people to think beyond what they think they know about the world.

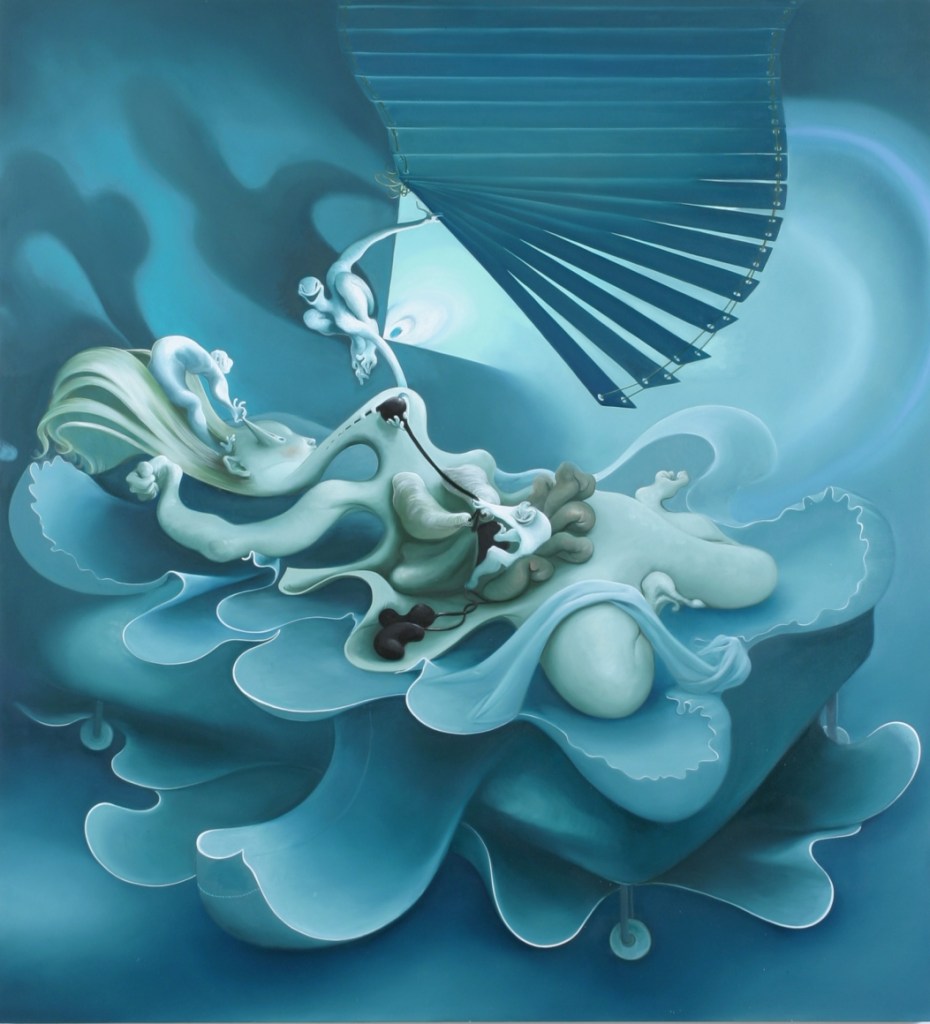

Unlike Dadaists, Surrealists consider themselves to be real artists. On the other hand, Dadaists’ art is meant to mock the art world; it is anti-art. Surrealism emerged not to mock, but to make people question rational thought. Surrealists’ goal was to make thought provoking work that makes you see the world in a new perspective. Also, although Dada and Surrealism came about because of World War I, dada was a negative and critical expression of feelings, while surrealism was a more positive expression. In other words, Dadaists used their art as an outlet to critique, and surrealists used their art to simply question. One example of this style of art is Lobster on Telephone (1938), a sculpture by Edward James and Salvador Dalí. The title describes the appearance of the work perfectly; there is a plastic, red lobster on top of an black rotary phone. These are two vastly different things that the average person would not think would go together. When asked why he created the piece, Dalí said, “I do not understand why, when I ask for a grilled lobster in a restaurant, I am never served a cooked telephone. I do not understand why champagne is always chilled and why on the other hand telephones, which are habitually so frightfully warm and disagreeably sticky to the touch, are not also put in silver buckets with crushed ice around them.” James and Dalí wanted viewers of the piece to question its purpose; was there even meant to be a purpose? Does all art have to have meaning or can it just exist for art’s sake?

Known for their humor and not taking themselves too seriously, Dadaism and Surrealism have many things in common and it is easy to see why they are often mistaken for each other. They also have many differences as well; Dada was more negative, meant to critique, and was anti-establishment. On the other hand, Surrealists were more positive, meant to inspire questions, and they were less involved in politics when it came to their art. Despite their similarities and differences, they are two powerful art movements that are still respected and discussed today.

Sources

Cramer, Dr. Charles, and Dr. Kim Grant. “Dada Readymades.” Khan Academy. Accessed on December 13, 2021. https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/art-1010/dada-and-surrealism/dada2/a/dada-readymades.

Ducahmp, Marcel. Pencil on reproduction, 1919/1964. Israel Museum, Jerusalem. https://www.imj.org.il/en/collections/199796

MoMA. “World War I and Dada.” MoMALearning. Accessed on December 13, 2021. https://www.moma.org/learn/moma_learning/themes/dada/

Riggs, Terry. “Lobster Telephone.” Tate Britain. Last modified March 1998. https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/dali-lobster-telephone-t03257

Samusevich, Alice. “Dada and Surrealism.” Eportfolios@Macaulay. September 23, 2009. https://eportfolios.macaulay.cuny.edu/weinroth2009/2009/09/23/dada-and-surrealism/.

Voorhies, James. “Surrealism.” Met Museum. Last modified October 2004. https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/surr/hd_surr.htm