The Yale British Art Gallery’s Art in Focus: Women from the Center is an exhibit that took place from January 14th, 2021-October 10th, 2021. It was curated by current Yale University students Emma Gray, Sunnie Liu, Annie Roberts, Christina Robertson, and Olivia Thomas. According to the curators the exhibit is, “Inspired by Yale University’s celebration of 50 years of coeducation in Yale college and 150 years of coeducation in Yale graduate programs, Art in Focus: Women From the Center highlights women artists whose inventive art practices have enabled them to stake out space in the art world.” An exhibit like this is very important, because it showcases the importance of diverse female representation in art. When discussing art history, women artists, especially women of color, are usually left out of the picture and men are in the forefront. Finally, women of all backgrounds are taking the stage and are finding their place in the art world. One unfortunate downside of the exhibit is that it felt incomplete. Walking around, there seemed to be something missing, as if some pieces were taken down. However, the artwork that was showcased makes up for this.

One of the first things that is noticeable about the exhibit is that it is more diverse than most. The art world is notorious for not being very inclusive. For many years, women and people of color artists have been excluded from art museums. According to a 2018 study done on diversity in museums, researchers found that in 18 major art museums, 87% of artists represented were male, and 85% were White. In this exhibit, there are pieces from artists who are women of color such as Joy Gregory, a Black woman, and Rina Banerjee who is Indian American. Often, non-white artists are not showcased as much in art galleries; especially in galleries that focus on British art, where work from white artists is usually prioritized. Yale made a genuine effort to include women from different ethnicities, which is appreciated.

The stand-out part of the exhibit was Women as Muses. The female muse is the most prevalent theme in Western art. Throughout history, muses have been idealized and objectified by the male gaze, but these works challenge our understanding of the relationship between the artist and the muse. Often in Western art, artists’ muses (who are mainly women) are subject to being seen purely as objects. The onlooker does not see the muse as a whole person, but instead, only someone to gawk at and admire. Muses can also be used for male artists to project their sexist feelings onto. An example of this would be Pablo Picasso and the many women who inspired his works. Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907) which translates to “The Young Ladies of Avignon,” is a painting by Picasso that shows unflattering depictions of his five female subjects, who worked as prostitutes. The ladies are posed naked together, their bodies are abstract form, and their faces are deformed with traditionally masculine features. This work has been criticized for being dehumanizing to the women, especially because of the stigmatization around sex work in the 1900s. When discussing the meaning behind the painting, Rachel Higson states, “In Les Demoiselles, the women working in the brothel have angular vaginas and powerful poses expose the dangers of liberated female sexuality. This painting is about women, not for women—a formula on which so many patriarchal institutions rely. The phallic orientation of the pear and apple at the bottom center of the canvas reveals how exposed the genitalia and in essence the male viewer is when up against an independent woman.” Many people feel that Les Demoiselle d’Avignon and his other works with female subjects tap into Picasso’s fear of women’s sexual freedom.

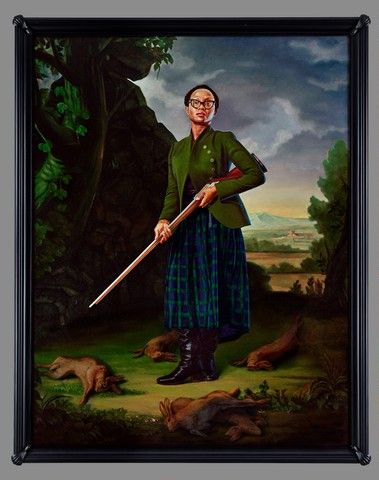

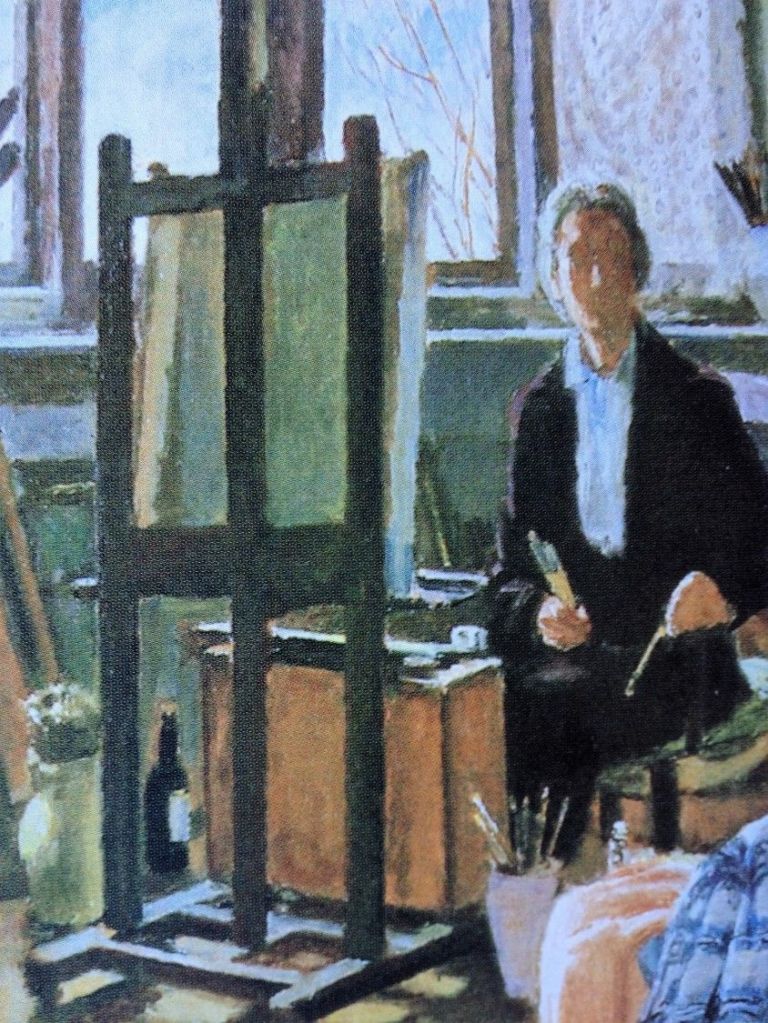

In Women as Muses, female artists are reclaiming their power and depicting themselves through their own gaze, also known as the feminine gaze. Vanessa Bell’s 1952 painting The Artist in her Studio shows the artist herself sitting on a chair in front of an easel and canvas looking back at the viewer. She is holding paint brushes, suggesting that she is about to paint something, or is in the process of doing so. The color palette is muted, giving the painting a quaint and still feel. Bell perhaps was inspired by looking in the mirror and decided to paint herself. She may have also wanted to showcase what her painting process looks like. Another standout piece in the exhibition is Neeta Madahar’s Sharon with Peonies (2009) This piece is a part of a greater collection of works called Flora, which contains seventeen images of Madahar’s friends. She describes the goal of this project as, “The portraits, shot in a style reminiscent of 1930-50s glamor images, are not concerned with nostalgia, but anchored in the present, aware that fantasy personas are shams that can be superficially occupied and manipulated in front of the camera.” In this photograph, a dark skin Black woman with giant cream-colored peonies in her hair, wearing an asymmetrical blue metallic top. Her head is turned to the side and her eyes are closed, with one of her hands on her chest. Rarely in famous historical pictures and paintings are Black women the muses; this photograph subverts that.

Women being included in the art discussions is extremely important. A gallery as influential as Yale highlighting women of all backgrounds will hopefully inspire change in the art world. Women in Focus, although small, is worth the trip to the Yale British Art Gallery. There are very compelling artworks, and there is also diversity and representation for all women.

Sources

Bell, Vanessa. The Artist in her Studio. 1952. Oil on canvas. 24″ x 20″. Yale Center For British Art, New Haven, CT. https://collections.britishart.yale.edu/catalog/tms:61974

Brooklyn Museum. “Neeta Madahar.” Accessed on December 13, 2021. https://www.brooklynmuseum.org/eascfa/about/feminist_art_base/neeta-madahar.

Higson, Rachel. “Reframing Picasso: Hannah Gadsby and ‘Separating the Man from the Art.’” The Prindle Post. Last modified August 2, 2018. https://www.prindlepost.org/2018/08/reframing-picasso/

Madahar, Neeta. Sharon with Peonies. 2009. Chromogenic print on photographic paper, 39 3/4″ × 30″ and 34 7/8″ × 28″. Yale Center For British Art, New Haven, CT. https://collections.britishart.yale.edu/catalog/tms:81309

Yale University. “Art in Focus: Women from the Center.” Accessed December 13, 2021. https://britishart.yale.edu/exhibitions-programs/art-focus-women-center.

Topaz, Chad M., Bernhard Klingenberg,Daniel Turek,Brianna Heggeseth,Pamela E. Harris,Julie C. Blackwood,C. Ondine Chavoya,Steven Nelson, and Kevin M. Murphy. “Diversity of artists in major U.S. museums.” PLOS One. Last modified March 20, 2019. https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0212852.